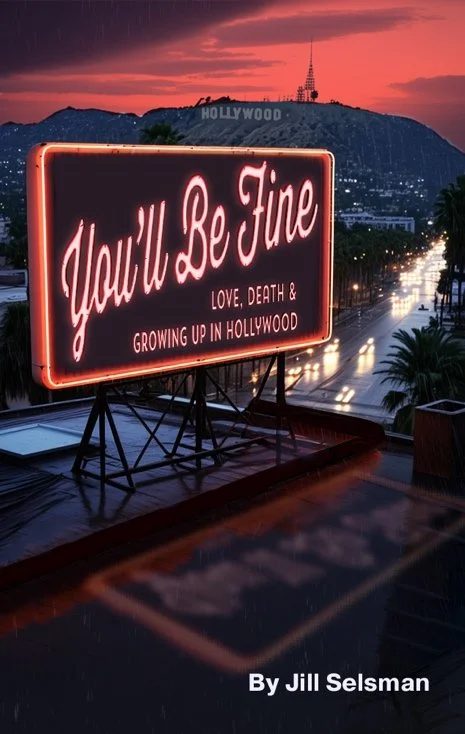

You'll Be Fine

Love, Death and Growing Up in Hollywood

A Hollywood coming of age story

What readers are saying:

“Heartbreakingly brutal and beautiful.”

“A mix of detachment, emotion, kindness and resilience.”

“Fascinating, intimate look into the nuts world of Hollywood stars.”

“Love that it’s chaptered by geography - emphasizes the exciting yet gypsy existence she lived.”

Jill Selsman, Author

AUTHOR BIO

Jill Selsman began her writing career as an editor and writer at Interview Magazine in New York City where founder, Andy Warhol was her mentor. During this time, Jill wrote for countless other publications including New York Magazine, NY Post, Italian Vogue and French Vogue.

After five years, Jill moved to London where she wrote news and feature stories for the Daily Mail and Tatler magazine. Jill then segued into broadcasting at MTV, writing the news and producing and directing documentaries. This led to Jill becoming Executive Producer of Content at MTV Indonesia based in Jakarta. She then launched the UK’s first 360 degrees channel, MTV Flux.

Jill eventually returned to New York City to become Executive Producer of Interactive with the Food Network, developing strategies and content for five new digital channels. Jill then created her own digital food channel, HangryTV through her boutique film and online media agency Ubilam Ltd. For non-dyslexics, Ubilam is Malibu spelled backwards. She’s obviously still very attached.

“Jill-ouise” at The Chateau Press: Vanity Fair, SF Gate and Byline

Q and A

Q 1: I was going to start with what’s in your bag, but I’ll stay focused on the project. I have to ask you, what was it like growing up in Hollywood?

Jill Selsman: My answer was and is always, it’s all I knew. Everyone I grew up around was in entertainment. My mother had deep roots in the community and if nothing else, was respected for being one of the ones still standing. It showed me that for an industry known for being fickle, people in the game may not have liked each other, but they respected the hustle.

What I capital “L” loved most about growing up in Hollywood was the endlessly flowing tap of creativity that I was exposed to. You could create an entire world out of pixie dust. Words on a page, that came magically from someone’s imagination, are brought to life by teams of creatives, hair makeup, staging, all the crew, and then they put the actors in and they deliver the experience. Being part of it showed me that through art, our life experience can be transformative and I have to thank my mother for showing me that. Everything else is… complicated.

Q:2 Why did it take you so long to write this book? The Chateau chapter came out in the late 90’s. Why now?

JS: Simple answer, the pandemic gave me uninterrupted time to focus. Previously, every time I worked with the subject matter, I’d have an incapacitating emotional collapse. My first pass was a short film script that I submitted to Sundance Writers’s Workshop decades ago. I was accepted, but didn’t follow through. The next version was the chapter published in 1999 in The Hollywood Handbook (Rizzoli). It was globally syndicated, the ’90’s version of viral, which led to publisher’s asking for more. So I started down the road of writing many chapters before I emotionally cratered again. Five years later, I organized that material into a foxy proposal, showed it to exactly no one and yup, cratered again. Then the overall life and death context of the pandemic somehow offered distance from the material. I wasn’t going to let the pandemic kill me if I could help it, so I decided that this time, I wouldn’t let writing this book kill me either.

Q 3: Your mother as portrayed in your book embraced constant change. It feels like stability was something she had to destroy to live a creative life, What was your experience of living with someone so unpredictable?

JS: The good parts were filled with a sense that something fun and exciting was always either happening or just about to. My mom was cool and she was young, super young. She was a curious person who was open to ideas and experiences and she always had interesting, intelligent people around her who vibed with her need to move at light speed. She loved Hollywood and being part of it. Hollywood was really the family that raised her. The bad part for me was constantly having to adapt to new situations, schools, countries, different cities, all of which left me with less energy for the normal parts of being a kid.

Q 4: Did you ever want to be an actor yourself?

JS: I definitely considered it and I knew I could do it intellectually, but I’m small and curvy, which is hard for the camera and I didn’t want to be in a profession where perpetually starving yourself is a job requirement. I was excited to see more and different body types on stage my teenage summer I spent going to Broadway shows and thought again, maybe. But a brilliant performance evaporates the minute you’re off stage and I decided I wanted to have something more solid for my efforts. Ultimately to be successful, you need to exist for and only be satisfied by the validation performing in front of an audience gives you. I don’t have that gene, but it does look like fun.

Q 5: Why did you decide to write this as a memoir, not fiction?

JS: I was a journalist, so I’m skewed to ‘just the facts m’am”. In ‘reporting it as memoir, I could relay the absurdities in a way that I’m just not skilled enough to do in fiction.

Q 6: How did you decide which parts of your life to include.

JS: There’s a lot of stuff that I had to take out to make it a cohesive narrative and not overwhelm the reader. For example, at the same time that the guy was stalking us, cutting our electricity and phone lines every 2 weeks, there was a massive earthquake, followed by massive flooding. I’ll eventually put them back in as bonus tracks in the collector's edition.

Q 7: Did you worry about how people in your life would react?

JS: Multiple perspectives are a given but I can only faithfully report mine. One of my all time favorite book titles is James Thurber’s My World and Welcome To It. It’s always been a shorthand for me for the multiple, extreme situations I was exposed to growing up. I can’t speak for any one else.

Q 8: How did you handle writing about painful or traumatic experiences?

JS: By giving myself lots of time and space as needed and by taking small manageable steps. I took a co-working desk which abstracted my writing experience. Listening to tech bros selling a new and exciting SAS product in the background was an excellent way to get overview on the story I was trying to tell.

Q 9: Did writing your memoir change the way you see yourself and your past?

JS: Not as much as you would want it to. Because I write for a living, I look at a keyboard and see deadlines and word count. I keep music industry hours and am at my desk from 10-6 with a solid lunch break. Inside that structure I try to make the words conform to the story I’m telling and leave them there when I close shop.

Q 10: Did you take creative liberties?

JS: The book is my experience, told from my point of view. I’m not trying to re-litigate the past and I hope it reads that way. Some names have been changed to protect the innocent and some stories have been condensed for pace as it is a creative endeavor, but it’s all true. Again, true if you’re in my body looking out through my eyes.

Q 11: What was the hardest and easiest parts of writing your memoir?

JS: Anywhere that I’m extra disempowered, where I’m struggling with forces beyond my control that are acting upon me, is always a tough space to go back into and write about. Parts that engage me, that I think are funny and tell a bigger story about life are a pleasure to write.

Q 12: What do you hope readers take away from your memoir?

JS: Kindness for yourself and others and the ‘if she can do it, so can you’ concept of finding a way through challenges. It is important to note that I have no special skills. I learned to stay on my game. I had to be clever and figure out where I was staying, how I was getting there and which restaurants we had a house account at so I could get dinner. It made me nimble and independent but also kind of exhausted. Our brains have a great capacity for generosity, use it on yourself and let it spread out. And if you’re telling your story, try and make it funny. People can accept a lot more information, good and bad, if you make them laugh.